Acute Coronary Syndromes

- First cause of death worldwide1

- About 5 million annual hospitalisations in Europe and the USA4,5

- Total annual cost: USD 270 billion in Europe and USA4,5

Definition

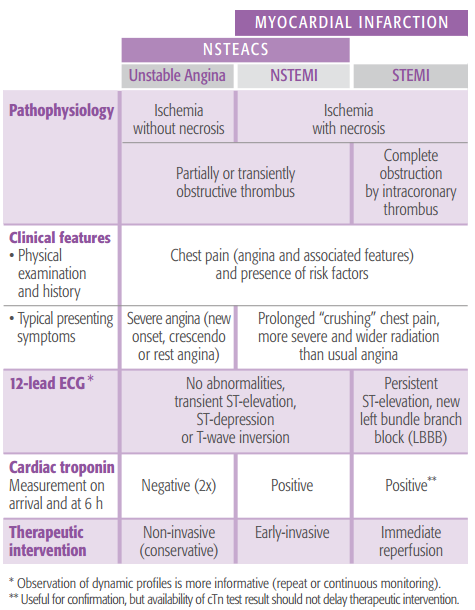

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) is an umbrella term for conditions caused by sudden blockage of the blood supply to the heart. They range from a potentially reversible phase of unstable angina (UA) to irreversible cell death due to a myocardinal infarction (MI) - either a non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) or a ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) (see chart below).

Distinguishing features of acute coronary syndromes*

Click to enlarge

*Chart from bioMérieux clinical booklet, “Biomarkers in the management of cardiac emergencies”.

Adapted from Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598-660.

UA, NSTEMI and STEMI have a common pathophysiological origin related to atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD), characterized by a plaque in the walls of the arteries that supply blood to the heart. Erosion or rupture of the plaque leads to the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) that blocks the flow of blood to the heart, starving it of oxygen and ultimately leading to myocardial necrosis (tissue death in the heart muscle).6

Diagnosis

ACS is suspected when a person presents with symptoms, particularly chest pain, and especially when they also have known risk factors like high blood pressure, being overweight or a family history.

Symptoms patients with ACS may experience include:

- Pain such as pressure, squeezing, or a burning sensation across the chest, possibly radiating to the neck, jaw or either arm

- Heart palpitations

- Sweating

- Nausea

- Dyspnea (difficulty breathing)

- Dizziness or fainting

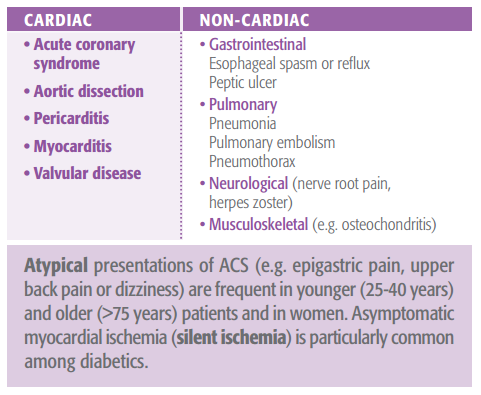

Causes of chest pain or discomfort

Rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical because myocardial infarction (MI) requires immediate intervention and prognosis improves significantly with rapid treatment3. However, this is not always easy because symptoms vary greatly. On top of that, there are many other causes of chest pain that are not ACS (see chart). In fact, as many as 8 out of 10 patients who come to emergency departments with ACS-like symptoms turn out not to have ACS2.

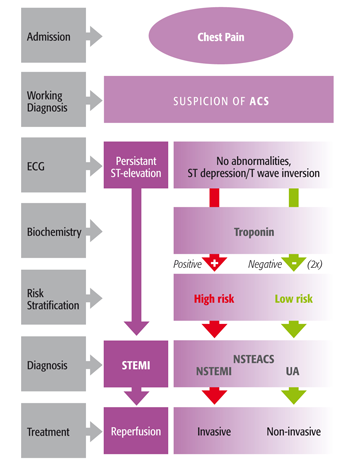

Approach to diagnosis and risk stratification of ACS*

Click to enlarge

*Chart from bioMérieux clinical booklet, “Biomarkers in the management of cardiac emergencies”.

Adapted from ESC Guidelines: Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, et al. Eur Heart J. 2007;28: 1598-660; Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999-3054

By performing an electrocardiogram (ECG) and measuring for a biomarker of cardiac necrosis (cardiac troponin), clinicians can make a diagnosis of ACS, and furthermore distinguish the disease into three categories: unstable angina (UA), non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), and ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI). A risk stratification score based on these tests is important to determine appropriate treatment.

- An electrocardiogram (ECG) can identify approximately 1/3 of ACS patients with persistent ST-segment elevation (STEMI).

- Cardiac troponin I and T (cTnI, cTnT) biomarkers help distinguish the 2/3 of ACS patients without ST-segment elevation (UA or NSTEMI).

- Cardiac troponin is the preferred cardiac necrosis biomarker, while CK-MB is an acceptable alternative when cTn is not available7.

- Serial measurement of cTn (on arrival and after 6 hours) is required in patients without ST-elevation on ECG7.

Sensitive and specific cardiac marker tests with a rapid turnaround time are essential to global risk assessment and treatment of all patients presenting with ACS.

Find out more about Cardiac Markers for ACS

Prevention/Treatment

Prevention

There are a number of known risk factors for ACS including:

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Being overweight

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- A family history of heart disease and stroke

- Older age

Prevention of ACS starts with healthy living and sometimes medication to lower risk factors. Some of the things you can do include:

- Eating a healthy, balanced diet

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Moderate physical exercise

- Controlling diabetes

- Taking medication as prescribed by a doctor to treat risks like high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes

Treatment

The distinction between ACS categories – STEMI, NSTEMI or UA –as well as an assessment of the likelihood of adverse outcomes is clinically important and drives the decision for timing, type and intensity of therapeutic intervention. To this end, a risk stratification score is determined integrating ECG, clinical findings and cardiac marker tests.

- A STEMI is a serious emergency and should be treated with immediate reperfusion – opening the blocked arteries to restore blood flow to the heart. The sooner this is done, the better the potential outcome. Once stabilized, treatment is aimed at preventing recurrence.

- UA and NSTEMI are emergencies and initial treatment is aimed at stabilizing cardiac ischemia – restoring blood flow to the heart. Generally, UA requires non-invasive treatment while an NSTEMI requires early-invasive treatment. Along with relieving pain, the goal is to limit or prevent progression.

- Medications that may be used in different combinations, immediately and/or later, to treat ACS include:

- Antithrombotic drugs (e.g. aspirin, clopidogrel, heparins)

- Painkillers

- Thrombolytics (clot busters) in the case of complete blockage (STEMI) and non-availability of angioplasty/stenting within 90 minutes

- Nitrates to widen narrowed blood vessels (vasodilation)

- Beta-blockers to lower heart rate, blood pressure and contractility

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for vasodilation and blood pressure lowering

- Statins to lower cholesterol

- Surgeries for ACS (either emergency or later to prevent recurrence) include the following coronary revascularization procedures:

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): angioplasty and stenting to open the blocked artery

- Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery to give blood an alternate route around the blocked artery

Guidelines

STEMI

- ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation

Steg, Ph. G. et. al. The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2012; 33, 2569–2619. Guidelines_AMI_STEMI.pdf - 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78-140.

UA/NSTEMI

- ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation

Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011; 32 2999-3054 - 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:e215-367.

Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction

- Third universal definition of myocardial infarction.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551-67.

Cardiac Biomarkers

- National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry and IFCC Committee for Standardization of Markers of Cardiac Damage Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: analytical issues for biochemical markers of acute coronary syndromes.

Apple FS, Jesse RL, Newby LK, et al. Clin Chem. 2007;53:547-51. - National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes.

Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al. Clin Chem. 2007;53:552-74. - Recommendations for the use of cardiac troponin measurement in acute cardiac care. Thygesen K, Mair J, Katus H, et al. ; Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2197-204.

REFERENCES

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006; 367: 1747-57.

- Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342: 1163-70.

- Nallamothu BK, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. Time to treatment in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1631-8.

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al.; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245.

- Nichols M, Townsend N, Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Scarborough P, Rayner M (2012). European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2012. European Heart Network, Brussels, European Society of Cardiology, Sophia Antipolis.

- Libby P.Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004-13.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551-67.

Az oldal tartalma nem tekinthető orvosi tanácsnak

Az oldal egészségügyi tartalma összefoglaló formában jelenik meg, jellegét tekintve általános, és csak tájékoztatásra szolgál. Az oldal szerzőinek nem állt szándékában és nem is ajánlatos a tartalmat professzionális orvosi tanács helyett használni. Az oldal egészségügyi tartalmát nem szabad egészségügyi vagy közérzeti probléma vagy betegség diagnosztizálására használni. Mindig kérjen tanácsot orvosától vagy más egészségügyi szakembertől bármilyen egészségügyi problémával vagy kezeléssel kapcsolatban. Az oldal semmilyen tartalmát sem szánták orvosi diagnózisnak vagy kezelésnek. Orvosok nem használhatják fel egyedüli forrásként a felírandó gyógyszert érintő döntésekhez. Soha ne hagyja figyelmen kívül az orvosi tanácsot, illetve ne halogassa, hogy orvoshoz menjen olyasmi miatt, amit ezen az oldalon olvasott.